Chris Dorland

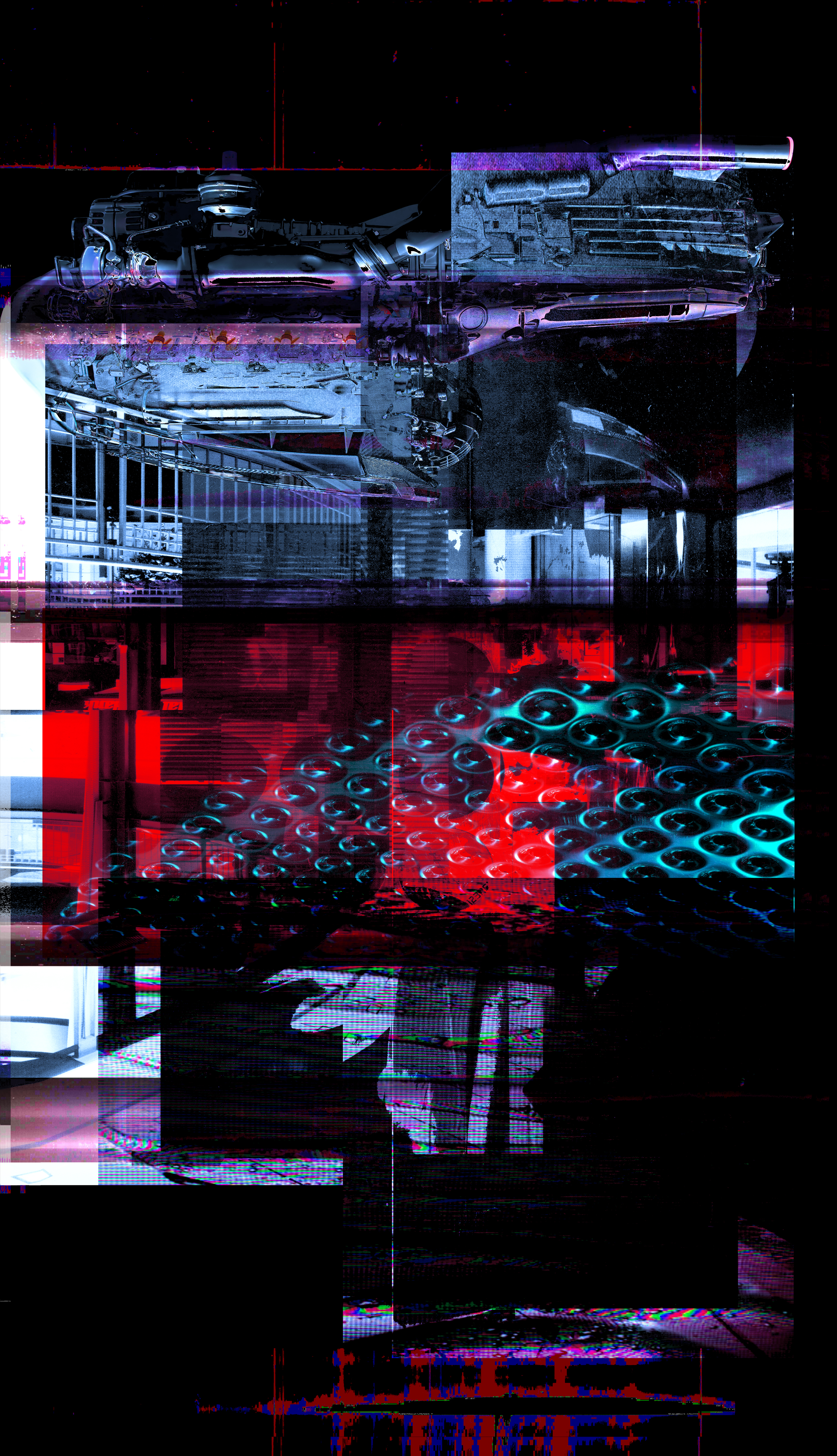

FLR-13, 2020

Super Dakota is pleased to present the fifth edition of our Super Stories. This week, we turn our focus to FLR-13, 2020, a simulated virtual environment created by the New-York based artist Chris Dorland.

As the 21st Century unfolds, the digital sphere is increasingly expanding to all domains, requiring a redistribution of the coordinates through which humanity could hitherto differentiate what is real from what isn’t. FLR-13 was created in this context in an attempt to conjure up the interstitial spaces where physical and virtual modes of perception interweave. The work enables viewers from anywhere with an internet connection to experience an innovative online exhibition and question the increasingly tenuous boundaries between current and established virtual realities in relation to social, political, and philosophical issues.

Chris Dorland, FLR-13

Chris Dorland’s FLR-13, 2020, was created in conjunction with his personal exhibition Active User at Nicoletti Contemporary in London (10.01.20 – 28.03.20). They are two interrelated projects: while Active User is an exhibition of new works – a series of new paintings and Alumacore panels – taking place in the physical space of the gallery, FLR-13 is a simulated virtual environment, including two videos piece. Moving through these liminal spaces, FLR-13 stands at the border between physical and virtual realities, objective truth and fantasies

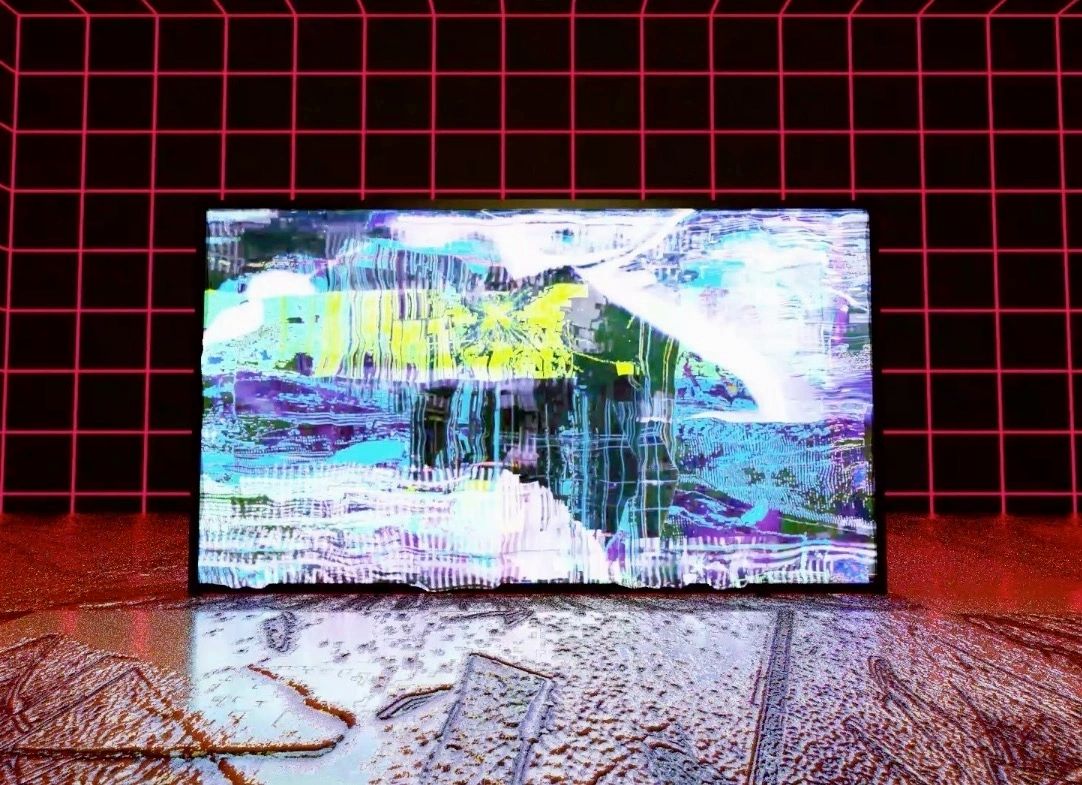

Exhibition view, Active User, 2020, Nicoletti Contemporary, London

Defined as “one of the most haunting VR shows currently online” by ArtReview, FLR-13 creates an innovative and exceptional experience allowing the viewers to experience the work by moving though a virtual dimension like a video game. The platform invites the player to walk around the space using its keyboard arrows. The space itself is dark and filled with neon-red lines that run along the walls. Several “interlinked CGI” rooms are available, in which we can browse and explore Dorland’s works. In his article, J.J Charlesworth writes : Dorland’s video sequences are shifting, flickering, stuttering collages of visual glitch – in the first space we ‘enter’ we see broken fields of algorithmic noise that then morph into more liquid, viscous forms, glistening like haemoglobin.

Copyrights Chris Dorland and Super Dakota

FLR-13 takes its title from the idea of the “Thirteenth Floor”, whereby countries viewing 13 as an unlucky number traditionally omit the thirteenth floor from multi-level buildings. Conspiracy theorists have suggested that the thirteenth floors in government buildings are not actually missing, but they would be hidden from the public eye as they would presumably contain top-secret information, or various other sinister hypothesis. FLR-13 refers to the 13th floor of highrises, which is often omitted as a numbered floor in some of the world’s more superstitious cultures.

The Thirteenth Floor, Josef Rusnak, 1999

Hidden, alternate-reality floors of buildings have a long pedigree of pop-cultural paranoia since at least The Twilight Zone episode The After Hours (1960). At Nicoletti Contemporary, Dorland’s ‘video artworks’ exist in this alternate-reality space – the gallery but not the gallery, and parallel a series of other works we see were exhibited in Dorland’s accompanying real-life exhibition Active User. FLR-13 is a homage to Philip K. Dick. deeply paranoid vision of how technology is on course to disintegrate the fragile distinctions between subjectivity, the body and reality. Its spectacle of infinite regress isn’t just about collapsing the material and the virtual, but a more disconcerting reflection on who it is that is doing the seeing, and where we (or they) are.

The After Hours, 1960, episode The Twilight Zone

Blade Runner 2049, written by Phillip K. Dick in 1982

“Today we live in a society in which spurious realities are manufactured by the media, by governments, by big corporations, by religious groups, political groups […] So I ask, in my writing, What is real? Because unceasingly we are bombarded with pseudo-realities manufactured by very sophisticated people using very sophisticated electronic mechanisms. I do not distrust their motives; I distrust their power. They have a lot of it. And it is an astonishing power: that of creating whole universes, universes of the mind. I ought to know. I do the same thing”

- Philip K. Dick

"Capitalism, in all it’s various manifestations. I’m basically fascinated by that. And have been since I was a little kid. The history of painting is a big influence also. Especially post-war painting. Also the Terminator- all the movies that have come out of that. The cyborg Hollywood apocalypse. Paul Verhoeven was a huge influence on me. His American movies left a very large footprint. They showed me that you could do a blockbuster but that it could also be critical and funny. I love his sense of sarcasm. David Cronenberg as well”

- Chris Dorland

Digital Dystopias explore how technology is transforming society and shaping our collective futures through dystopia (potential abuses, data, sociability…). The issue is that society is approaching a crossroads, where one digital route could take us in the direction of a utopian future and the other towards a dystopian one.

"First of all I should say I think my work is very urban. It’s the byproduct of someone who has lived their entire life in city centers. I’m interested in how personal desire and corporatized space work together. A question I ask myself a lot is where, within a very large and complicated matrix, do we locate ourselves? In a world where technology and consumer space have unimaginable levels of (unseen) control- what is left and how do you find meaning, and personal freedom, within that.”

- Chris Dorland

Lana et Lilly Wachowski, Matrix, 1999

Chris Dorland’s work is a dystopian vision of the human-built world filtered through the sublimated violence of abstraction, consumerism and technology. Working with a variety of screens, scanners and drones, Dorland is interested in the ways in which machines increasingly perceive, record and reproduce the world through data visualization, scanning hardware and other optical devices. Dorland’s role in the studio becomes that of a technician as he moves between the scanning devices and printers, allowing the various machines to document, distort and produce new images of the world.

Also alternating between software and analogue techniques, Chris Dorland operates montage from a voluminous archive of print and digital visuals that document our consumerist culture. After scanning, filtering and altering content through many digital manipulations, the artist prints out images which he reworks manually with various machines. A variety of outdated and old scanners, hand-held scanners, different types of printers and other obsolete technology inhabit his studio, making it a marvellous place for experimentation. “The studio is offline. Nothing is connected to the internet (including my desktop). I hate software updates, so in some cases, I’m running really old programs and hardware,” insists the artist who instead challenges devices to generate randomness, elements of glitch and other failures, defining his distinct aesthetic language.

Detail, FLR-13, 2020

“I’ve always been interested in the relationship between painting and technology. My work has developed into something I think of in terms of “screen based painting” or “software based painting”. I’ve been increasingly thinking about Artificial Intelligence and machine vision. What interests me is to articulate the technological screen as a surface and vehicle for painting. This has inevitably meant moving away from the canvas and shift even more aggressively into employing technology in all of the stages of the production process–whether it be using drones to capture imagery or working with programmers and animators to help generate new images. ”

- Chris Dorland

The concept of video games as a form of art is a commonly debated topic within the entertainment industry. Video game art relies on a broader range of artistic techniques and outcomes than artistic modification and it may also include painting, sculpture, appropriation, in-game intervention and performance, sampling, etc. Virtual immersion becomes total when digital works are presented online. FLR-13, 2020, demonstrates that a new genre can be created: virtual arts in a virtual gallery, while getting a unique experience, such as a video game, from our screens. Through this work, Chris Dorland highlights the paradoxe that arises when one can not experience an exhibition in real life and becomes a character in a virtual reality.