Julia Wachtel

Sunday Afternoon, 2017

Super Dakota is proud to present Super Stories, a new online format we are developing as the gallery goes into lockdown again. Continuing our tradition of in-depth researching we turn our focus to one single piece. Each week until Christmas, we chronicle the history of an important work of art. A piece we love and share with you.

The first piece is Sunday Afternoon, 2017 a major painting from the American artist Julia Wachtel. Its relevance regarding the current political climate in the United States, environmental change, globalization – and the way of life that goes with it – seems to be the perfect opportunity to present the story behind this painting.

Julia Wachtel

Sunday Afternoon, 2017

Oil and acrylic ink on canvas

152.4 x 403 cm / 60″ x 159″ inch

Sunday Afternoon was first showed in the exhibition Displacement, 2017 at the gallery Elizabeth Dee, in New York, one year after Donald Trump’s election. Sharing the room with other paintings that addressed notions of the social political American landscape, the exhibited paintings touched multiple aspects on the realm of culture that were affected under the new temporal mark, which was Trump’s administration. As stated in the Press Release at the time, the exhibition evoked matters such as: “marketability of “fake news”, tech’s monopoly in global business and social media, financial hacking, political interference, the Republican conservative agenda, the Second Amendment, global warming, entertainment and television, racism and sexism.” According to the artist, Sunday afternoon, 2017 and the body of work she created for the occasion addressed the feeling she had when Trump was elected, “I felt like the way I did after 9/11, that it was a kind of paradigme shift, kind of a monumental change, cultural change. I felt like I couldn’t make art that somehow didn’t address that situation.”

Installation view, Displacement, 2017, Elizabeth Dee, New York

Wachtel’s oil, acrylic, and silkscreen-on-canvas paintings, drawn from popular culture, explore the impact of our contemporary, image-saturated, world. A figure of the Pictures Generation artists who emerged in early-1980’s in New York, Wachtel’s early work mined posters of movie stars, pin-up girls, political figures, and pop music icons, as well as cartoon figures drawn from commercial greeting cards. Her current work primarily explores the vast space of the Internet, a place of constantly replenishing images on a disorienting scale. The artist appropriates, juxtaposes and ultimately distills these images into concentrated paintings, shifting the original logic and proposing an examination of the emotional, political and aesthetic conditions of an image dominant world while addressing the significant shifts of our time.

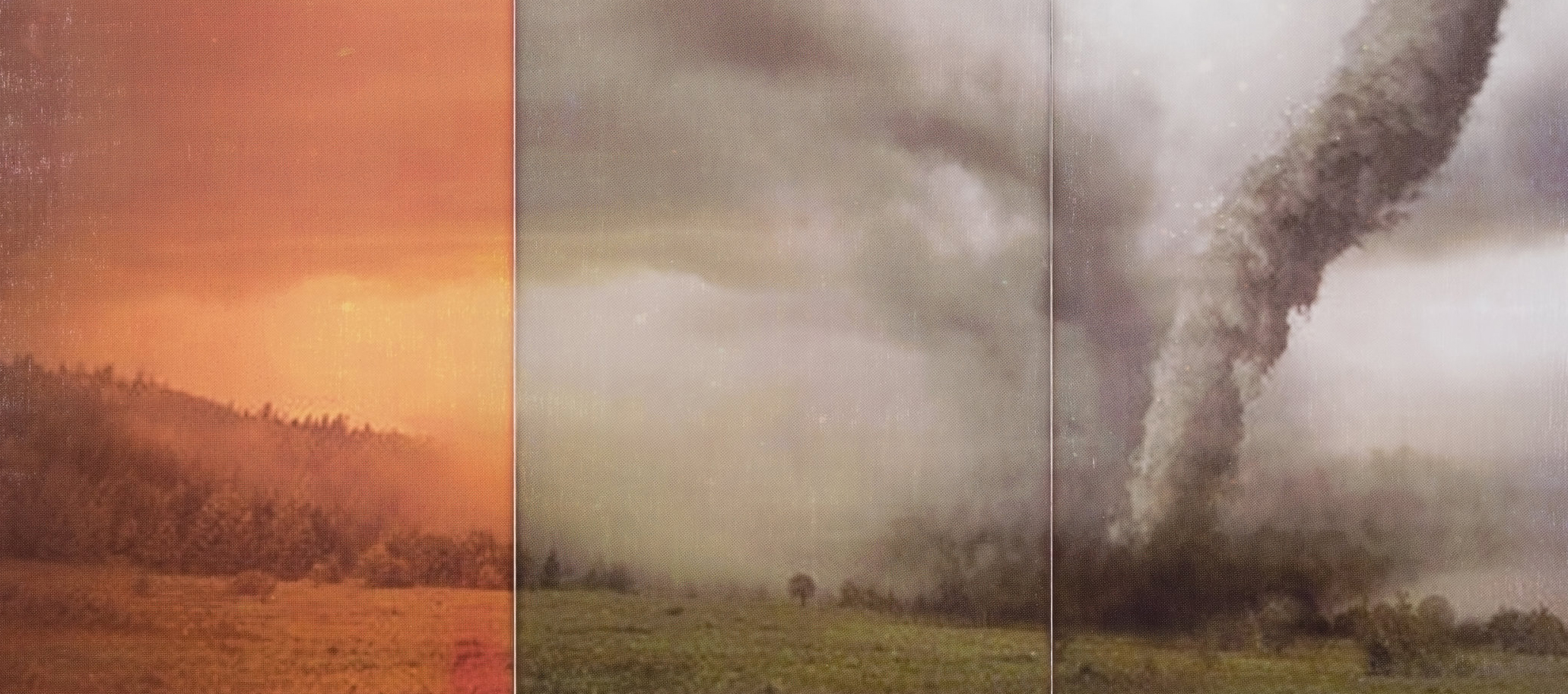

Sunday Afternoon, 2017, depicts the confrontation between a celebratory and unaware American way of life and the force of nature upon humanity. A bright colored landscape illustrates a hurricane silkscreened on bright vivid colors that becomes more and more pale until reaching a complete black and white pallet. The figure of the hurricane is juxtaposed to the image of a symbol from American culture: A hamburger, dressed in a 4th of July costume, smiling at the viewers.

Jasper Johns, Flag, 1954-55, MoMA, New York

From the left to the right, the color scheme goes from a hot palate as if the scenery was on fire to a neutral, “without filters”, treatment that fades away until the complete absence of color. The viewer is confronted to the encounter of a duality: A natural phenomenon such as the tornado – which is an element that is part of the American landscape, not necessarily associated with climate change but threatening enough since tornadoes became a frequent event due to global warming – and a cultural icon, which is the American burger (the main symbol of fast food in America, the most common dish associated to the country, so appealing it became an international hit). This contrast ends up making the viewer wonder about the consequences of such association.

“I decided I wanted to use the image of a tornado for several reasons. Number one, a tornado in this country has a lot of American narrative behind it that’s not associated with climate change. I liked that about it. Think of the Wizard of Oz, being a very iconic movie with the tornado coming through.

I also liked the fact that a tornado in and on itself is kind of a figurative thing. In fact when I first started looking for the cartoons, I found millions of cartoons of tornados that are anthropomorphized. (…) Then I needed to find something to pair it with. I forget exactly how my search progressed, how I came upon this hamburger but when I found it I thought it would be perfect, I just loved the way it looked. It is Fourth of July with the Uncle Sam hat, the sparkler and the flag and a hamburger. It’s evocative of picnics, fast food… It kind of resonated in multiple directions that I liked.

The association of that kind of happy event or, a picnic, when everyone is outside celebrating and then to place it in this ominous landscape with the hamburger being unaware of the impending doom coming upon it, metaphorically by the tornado. Just seemed like the perfect metaphor for where we were in this country.”

- Julia Wachtel

Environmental issues are a quite recurrent theme when looking at the artist’s body of work. “For this painting in particular I wanted to deal with climate, which I tend to do with almost every show - I will have some painting that somehow deals with issues of climate change.”

- Julia Wachtel

Wachtel’s paintings are often big scale works. The important size allows the viewer to plunge in the depicted narrative. “In terms of the scale, the painting just has to be big enough so that you feel like you’re immersed in the landscape itself. To have that kind of one to one scale with the viewer and for the cartoon, it’s obviously small, well its not a person either, but for it to feel like a human scale, event though is it a little bit smaller than that.”

Looking back into Art History, important size paintings were reserved for Historical paintings, which were perceived as the most important type (or ‘genre’), of painting on the XVIIth and XVIIIth Century. Initially, the subject matter at that time was drawn from classical History, mythology, and Biblical scenes. It was only with Modernism, in the late XIXth Century to mid XXth Century, that this hierarchy of ‘genre’ was subverted. Interested in depicting light and personal impressions over landscapes, the Impressionist artists started to paint outdoors thanks to the modern invention of portable paint tubes. The title of Julia Wachtel’s painting Sunday Afternoon, 2017 references Georges Seurat painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte , 1886. Major figure of Post-Impressionist art, Seurat was interested in exploring the effects of colors in his painting and finding rhythm to the composition while implementing a completely new technique called “divisionism”. The technique might have been new but the main subject of interest was still the same when compared to the impressionist, and to contemporary artists: addressing the now.

Georges Seurat

Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1886

Through her paintings, Julia Wachtel explores the increasing importance of visual media in modern communications and the inability to differentiate between sign and reality.

Combining critical and humorous spectacle, Wachtel chooses a multipurpose visual vocabulary to refer to the serialization of banal and iconic images to test our sensorial empathy towards ‘authenticity’ and ‘truth’ in the complex interchange of images and messages. Her use of cartoon characters function as commentators or unwary conspirators on the social, political and cultural content surrounding them.

Julia Wachtel, Opening Day video, 2020

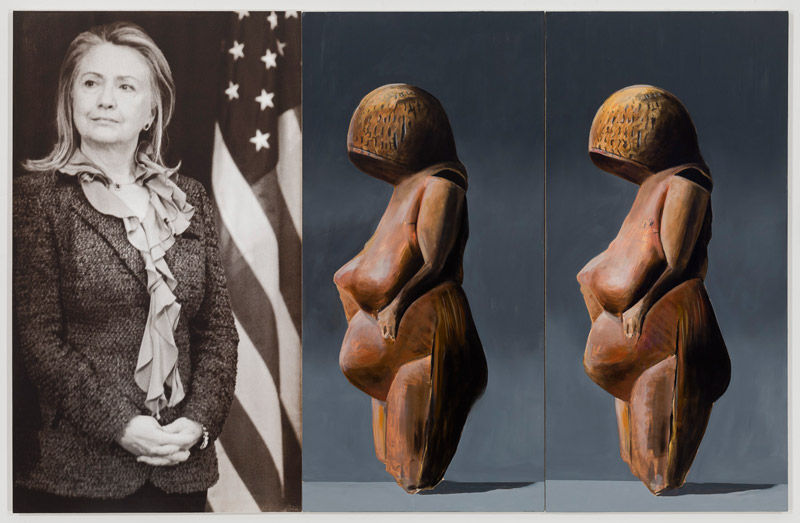

Julia Wachtel, Spirit, 2014

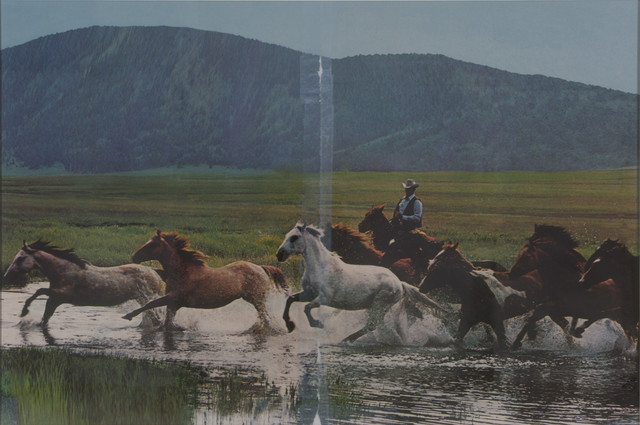

The very premise of appropriation art is political. The term emerged in the U.S. in the early 1980s to designate the international borrowing, copying, and alteration of preexisting images within the frame of Post-Modernism. The concepts of originality and of authorship are therefore central to the debate of appropriation in contemporary art. Keeping a critical distance while also consumers of those images – that populate visual culture, manipulate notions of identity and social relations – artists such as Richard Prince, John Baldessari and Barbara Kruger saw the artistic potential of re-contextualizing them, allowing the viewer to renegotiate the meaning of the original in a different, more current context.

Richard Prince, Untitled (cowboy), 2016

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Permanent collection

One cannot speak of appropriation art without mentioning Andy Warhol.

"[His] practice reveals a profound social and technological complexity. (…) Like Warhol, I use silk-screen, a technology made for seriality and reproduction. Unlike Warhol I always pair the silk-screen panels with at least one hand-painted panel. I sometimes duplicate the hand-painted panels, shifting the logic so that the hand-painted panel becomes the repeated image. They are nearly identical but it is their difference, and failure of perfection, that interests me."

- Julia Wachtel

Andy Warhol, Jackie, 1964

Julia Wachtel, Membership, 1984, exhibition view Fast Forward: Painting from the 1980s, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2017

Even though the artist makes use of the premises of appropriation art, it seems more pertinent to consider her work in relation to everyday life today, as we are overwhelmed with imagery more than ever. Her most recent body of work forces the viewer to reevaluate their motive for looking. As Quinn Latimer points in her essay (1): ‘Wachtel’s juxtapositions not only tackle but also transcend issues around the significatory power of existing images and the politics of their appropriation, thereby taking on our “emotional and economic investment” therein.’ Ultimately, Wachtel’s new friezelike compositions contribute to make sense out of this constant flow of information where she, herself is “trying to deal with possibilities and impossibilities of expression within a cultural context that to a frightening degree produces synthetic expression”.

(1) in the book Julia Wachtel published by Yale Press for the Cleveland Museum of Art, 2014